Underpainting for a pastel still life that could be an abstract painting as is.

That's a serious question, by the way. You might be hearing something I did from friends who critique, especially if you're fond of certain mediums such as colored pencils, oil painting, some styles of acrylic or watercolor or graphite drawing with a lot of fine detail. "You could loosen up and start getting more painterly. Less is more."

Lot of good that comment does when you don't know which details to leave out!

There's a good reason to learn detailed, accurate drawing, realism in tone, value, color, texture, everything. Even to follow a photo reference slavishly with great and loving care, measuring everything twice with a grid or the "tick marks" method (choose dramatic key points like eye corners, mouth corners, edges that turn or change shape, make a dot on the dark side and follow the edge of light and shadow or hue change with a flat or shaded area of rendering.) Or you trace carefully and then render.

Realism and photo realism are a crossroads.

For some artists, they aren't just a crossroads. They are the destination. These artists go from very carefully copying and following the photo in archival art materials, scaling it up or down (especially up) to taking their own photos. Their photos get better and better till they become photorealists. To become a brilliant photorealist, you need to learn accurate rendering AND good photography, have an eye for the image that's going to look even better enormously larger than life and master one or more mediums that can render it.

One noted photorealist was so careful about hand rendering from his photo reference that a critic complimented him for including a JPEG artifact - a light-color effect that was a side effect of using a high resolution digital camera before rendering the powerful image as a very large mural. Gee. Pixels the size of small brush strokes might actualy work, you know? Pointillists have been doing that since Seurat, who predated digital photography!

Maybe that's you! Maybe that's your style and who you are, while everyone who's trying to encourage you to more expressive, visible strokes and broader strokes, conciseness, simplification and so on is leading you on a path not yours. This happens. Your style grows out of who you are and what you love. If you really like to see realism so good people think it's a photo - you can also get so good at rendering life drawing that people think you had a photo reference when you did it.

You could wind up like the great graphite artists who wrote several of my drawing books and copiously illustrated them with trompe l'oeil graphite realism. Black and white photo thumb tacked to a piece of wood with a bit of chain dangling off a push pin, an old shoelace, a few keys, a button with a pin stuck through it... maybe a chandelier crystal... a still life in the vertical. In graphite it looks like a photo of the stuff.

But it's actually better than the photo, unless the photographer is a truly spectacular artist and photographer. The eye can capture nuances the camera can't. You have binocular vision and hands. The camera is monocular and distorts things. It has limited memory compared to you, the human artist. There was fantastic realism in the Renaissance when the only camera was tracing from a camera obscura. You can get the proportions that way or grid or learn to eye them by long practice and lots of sketching. Many ways to scan that cat.

That's where I thought I was going with art back when I was primarily a colored pencils artist. I loved colored pencils realism and still do. It still delights me to see realism done well. It's wonderful and you can do things with it that cannot be done with cameras.

The people who do it for the movies, or illustrators like James Gurney, can turn that kind of realism into a camera to carry inside your head. Dinosaurs can strut with ornate howdahs on their backs and steampunkish colorful people coexist with them to talk to them. Rockets soar and vampires sweep through the night, flower fairies come up in your garden, all myth and legend are yours to paint.

From there some artists stylize and follow this or that style of illustrator. They may go in the direction of comics (or start there) whether Western or manga. They may want to create illustrations or study commercial art for a good job. It's a good use for it, as good a use for art as any. The Sistine Chapel was a high paid illustrator doing a story the patron wanted told in the cathedral!

But head toward Fine Art and someone's going to say "You ought to loosen up."

Maybe that's you. Maybe you look at a Chinese painter's three stroke koi and gasp in wonder, because ink just exploded into as true a likeness as you'd get in some forty hours of straining and measuring and checking. Maybe you look at the Impressionists and want that crazy light and color streaming through your work... maybe there's more than one style that appeals to you. But one thing's for sure. You are not there yet and afraid to take the plunge. It's a scary plunge.

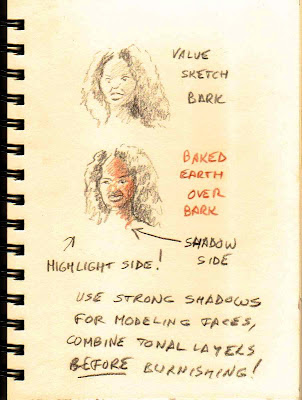

Because one of the best ways to get accuracy is to choose a detail like the size of one eye and measure against that to get the proportions of the nose, the placement of everything else, width of the mouth, side of the face, top of the head, everything. Do that carefully and you will have the likeness, especially with tone rather than line.

This is where "too perfectionist" comes into it. It's a matter of word choice. Seriously.

Until you master realism to the level you are satisfied with it - you, not your art teacher, your parents, your spouse, your friend, the gallery guy, the critic, the artist friend who thinks you could loosen up - there is a natural frustration at every single proportion error or rendering error of any kind.

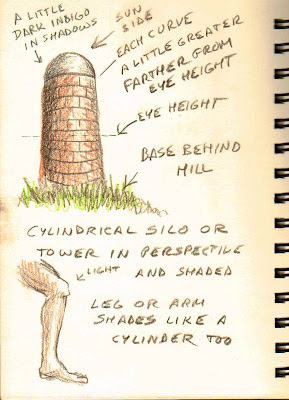

You might have a beautiful, expressive, gorgeous painting of a vase of flowers that everyone loves. Someone paid you a lot of money for it. And something about it gnaws at you. Because it was the curve of the bottom of the vase sitting on the table, an inaccurate ellipse, that curve was more shallow than the curve of the top of the vase but it's farther from eye level. The illusion breaks, it doesn't look real. The curve of the ellipse is rigth on one side but wrong on the other. And no one cares but you, because, the bottom of the vase is down at the bottom of the picture and you sensibly didn't give it a lot of contrast to distract from the main subject. The composition's fine. It's that stupid ellipse curve again, even after you read about ellipse curves and did exercises and tried to beat it into the stupid little animals at the ends of your arms that they go this way not that way.

Believe me, I have done that one when I knew better. Knowing better comes way before your eye knows and you can see that's what's wrong. You might think the vase isn't shiny enough or the loose stroke for its highlight is too distractingly ugly or the shadow isn't shaped right... but it's the dang ellipse curve again.

Or you got the ellipse but the shadow looks wrong, because it isn't the same direction as the light on the flowers. There are a thousand different rendering tricks to get realism and accuracy. When you master all the ones you need, you can go on to try to simplify what you paint.

It's also very vague to say "Simplify it and leave out what isn't important."

Yikes! You have to decide what's important or not! Oh boy! How do I tell people what's important or not? Maybe the viewer likes trees more than clouds and I should get the trees right, maybe they like the green one between the orange ones more than the orange one, those blobs don't look like foliage, how do I know how many leaves to put before the whole thing looks like a piece of leaf-stamped cloth instead of a clump of foliage. How did that impressionist actually do a blob just as blobby as mine and it looks like a tree?

Uh, you have to learn a bunch more tricks for that simplification too. Like the one about "Contrast draws the eye" and "Bright colors draw the eye" and low contrast and dull colors belong around the edges and in the backround. You need to learn a bunch of staging tricks to make the scene or person or animal look real - and they are not all about getting the shape of the nose right. Some of them work even if you get the shape of the nose completely wrong and paste it on the side of the face like Picasso, which is why he's famous and we're not.

It's hard to break the rules until you know the rules. On top of that, it helps to know why the rule is there so that you can break it on purpose to get attention by doing it exactly when and where it works. Making the exception to the rule a thing that makes the painting exactly what that one should be.

It leads to purple grass and turquoise in the leaves and pink in a blue sky. It leads to visible broad strokes that carry meaning and a swirl of paint or pastel dust that somehow gives the impression there is a living, moving fish gliding through water that's real even though it was three splashy strokes with a soggy brush. Or three or four pastel strokes dashed in.

It's being able to change the photo plausibly. Take a photo of an old person and make a picture of the teen they used to be. Take a photo of a winter tree and dress it with foliage in summer rain. Art is visual fiction. It's not the same thing as what you paint, no matter how accurate your realism - and the best realists are using all the same simplification tricks as the concise loose painters.

They just do it with a different choice of tools. The edge of the cork board in the trompe l'oeil painting hasn't got as much contrast or interesting objects and there are pointers leading back in to get you looking at the clear push pin and the shiny keys. So go ahead and draw clear push pins in your art journal. Sketch birds from photos including blurry wings if the bird was moving. That will actually work in a painting too. Sketch and draw things from life whether it's junk on your desk or what's outside your window while you're doing something else.

Paint. Lots. Practice. Read books, take classes, read articles, try anything and everything. Only you know when you've had enough realism and want to leave the crossroads for the direction that's right for you. You might abandon it fast for a primitive style as you develop exactly your stylized way to draw grungy unshaved characters or wide-eyed doll-faced mermaids.

You're you and style is something like your handwriting. You have it whether you plan to or not. The more skilled you get at drawing and painting, the easier it is for anyone else to recognize your style in everything you create.

I change around what mediums I use fairly often, especially from among those that fit in my lap on sick days. It may depend on the weather exactly what medium I do, because some days I've just really got to get it done in five minutes or I'll never get back to it. Others I might have a whole hour. Others I might spend all day or several sessions to finish it - that's disability setting limits. One of the best Impressionists I ever knew was legally blind. She painted what she saw, literally, and leaped right to color and light because for her the world was that colorful blur that makes sense. The details that distracted me to perfectly rendered petals and stylized awkward leaves weren't there in her vision.

How tall you are affects it. How you feel today. What you like in art. What you like to read. What you like to eat and whether you have an allergy to any solvent or to pastel dust. Whether you love tramping around in the snow painting plein air in the mountains or you need to stay in the car to paint that winter scene.

And of course what you like to read and who you love and what you think of life and the world and your loved ones. Most of all what makes you happy or angry or sad, your feelings come into it. If you love something, spending fourteen hours gazing at it and slowly going over it in Prismacolors realism is a day well spent, a happy one. If you don't have the patience for it any more, like me, it's because something interfered to make that less fun - like chronic fatigue. A bit too sick and I don't want to paint any more. But when I was one stage less disabled, Prismacolor realism got me sitting still happily for a dozen hours at a time and the results were very textured, detailed, colorful and rich.

I loosened up, partly for love of Impressionism and partly because I now need magnifier glasses to see my previous level of detail. As a child I did inch wide drawings with a 6x0 Rapidograph and they were accurate if it was a subject I had enough practice with.

Be you, learn, enjoy and know the crossroads after you leave it. There's a point at which it stops being very hard and becomes something you can trust. It came for me more than once, subject after subject. Earliest was sketching my pet white rat in pen, I developed a good pen texture for white fur (outlined with little dashes that went the direction of the hairs), dotted lines for the pretty little pale nose and muzzle, outlined big dark eyes, outlines where the crease of the ear made a line, a slightly broken line for his tail and accurate tail gestures. I learned how to do his tiny knuckles and claws. It was practice and observation, so drawing from life is probably the best way to get there - but reading and looking at art and classes are good too.

There's more to learn about how to paint and draw than any one person can do in one human lifetime. More gets invented every year and you'll make discoveries or rediscoveries. That's what it is, it's not a zero sum game. It stays challenging and fun because you'll always keep getting better, moving from the crossroads in the directions you want to go. That's the key to a strong personal style - just be you and work in the mediums you love, subjects you love, ways that you love.

If that's realism, more power to you. If it's loose or abstract you will get there when you do, and you are the one more than anyone who knows it. You couldn't have convinced me to give up realism for impressionism in the 80s, but here I am doing it and loving it - and still going back to pen-watercolor accuracy every now and then because I still love that too.

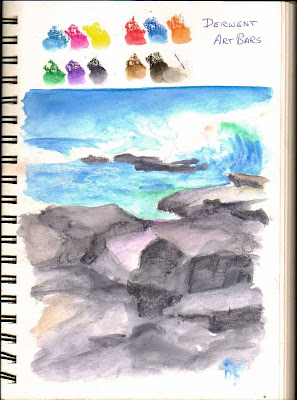

Pacific Wave

Above is the best ocean wave I've ever painted in my life. It looks very detailed but I did it in ten or fifteen minutes without hesitation, without planning, just looked at the reference and made decision after decision to change it. I paint better than I used to but not as well as I will.

Next week or month or year that'll happen again and maybe I'm ready to paint waves from life - they don't hold still for painters the way photos do.